Climate Tech’s Four Valleys of Death and Why We Must Build a Bridge

We need faster and more climate-tech innovation.

For such technologies, it’s an especially challenging path from idea to first product to broad deployment. Solar PV, wind, or electric vehicles experienced long and arduous journeys that spanned decades and even generations.

But why does it take so long to commercialize climate technologies? What barriers does a climate-tech entrepreneur see along the way? And how do we overcome these barriers and fast track climate-tech solutions to scale?

The Plain Truth: VCs Haven’t Loved Climate Tech

Silicon Valley has refined and perfected venture capital for software. This allows rapid innovation and scaling of new ideas—e.g., social media, digital payments and telecommuting. However, climate tech has a journey to commercialization that looks fundamentally different than software-driven tech innovations.

For a software tech company, the startup valley of death is the famed J curve. The oversimplified version reads like this: there is usually that one kiss-of-death experience, when the young startup is trapped in a trough struggling to find the winning route to market, but once she nails that product-market fit and gains enough momentum, it’s mostly smooth sailing from there.

That is precisely why, for a venture investor who focuses on pre-revenue or early-revenue software-driven startups, a great deal of due diligence involves understanding the founder’s ability to find market traction and make it out of that single valley of death.

However, finding that path is not as simple for climate-tech startups, especially for hardware or hard science plays. Climate-tech entrepreneurs are challenged by the realities of operating in a world where technical, commercial and regulatory expertise is a prerequisite, where product development takes longer, where incumbent inertia is greater, and where capital requirements are higher. Physical system transformation simply takes much longer than software deployment.

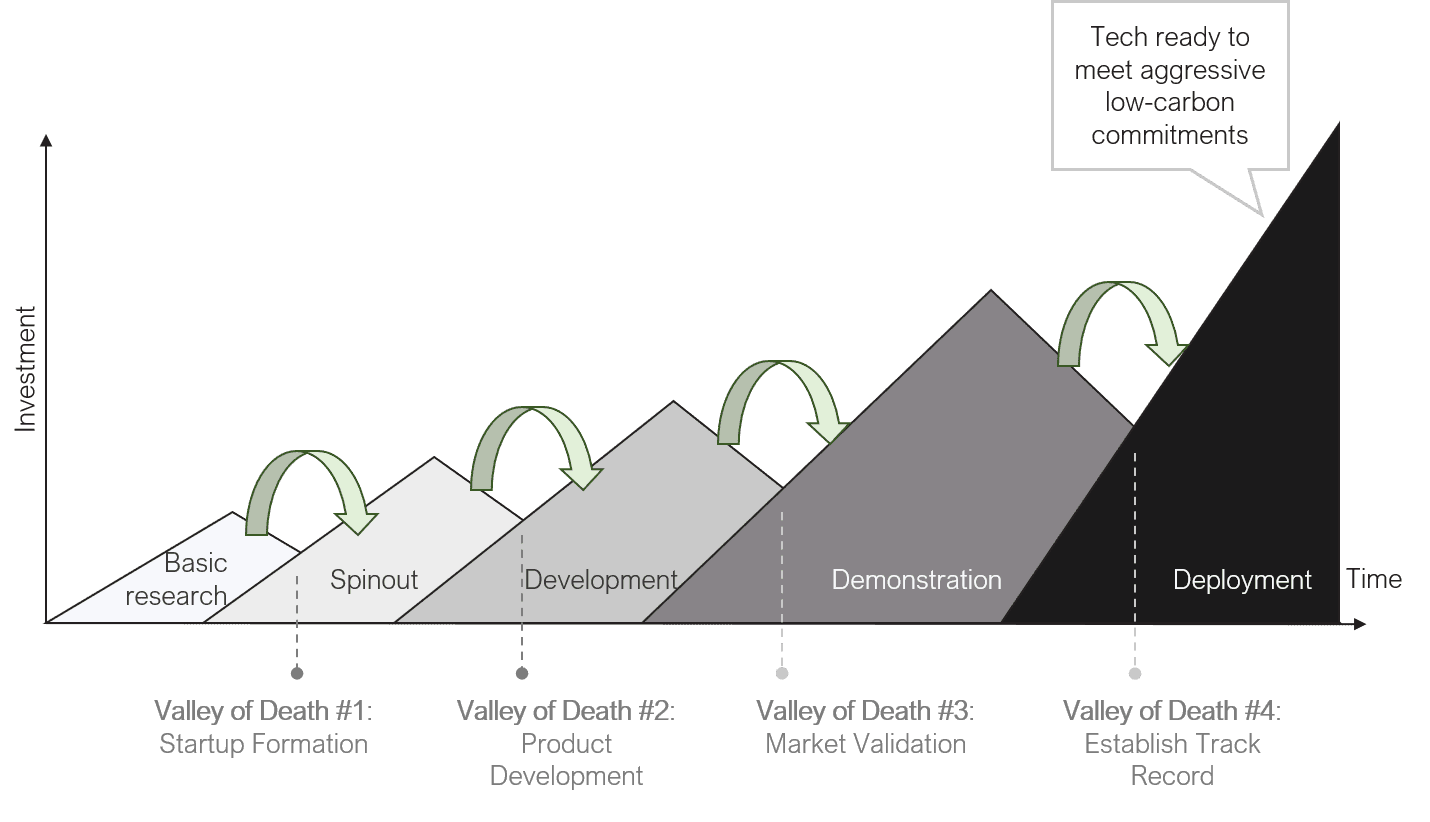

A climate-tech entrepreneur is faced with four great valleys in front of her. To cross these valleys, she needs to work with engineers, corporations, and investors with wildly different risk and reward appetites. And this is a significant problem for an investor of pre-revenue or early-revenue startups. When these early-stage venture investors have a hard time grasping how a startup can reasonably cross from one valley to the next and then the next, they fail to see a path to exit, and therefore hesitate to invest. When startups can’t attract investment, their vision crumbles.

So what are these four valleys of death? And what are the biggest challenges at each?

The First Valley of Death: Spinning out the Technology and Forming a Startup

Not enough transformative climate tech out of universities and national laboratories is launched into startups.

For investors wanting to support such early-stage technologies, the diligence required is significantly greater than for mature technologies, yet the amount invested is much smaller and the risk greater. Accordingly, most investors do not invest so early. This lack of capital and risk results in a dearth of experienced executive talent and causes new startups to rely instead on inexperienced recent Ph.D.s or postdocs serving as management teams.

This chicken-and-egg problem, where lack of start-up funding and few success stories discourages climate-tech researchers to take on the enormous risk of being a startup entrepreneur, is why not enough transformative climate tech is launched into startups.

Second Valley of Death: Finding Product-Market Fit and Launching a Minimum-Viable Product into a Complex Market

Many seed-stage climate-tech startups struggle with producing their first minimal viable product, in part because it is very hard to perfect their entry-point product-market fit.

Playbooks for direct-to-consumer or software startups are well established—e.g., lean startup, rapid prototyping, and agile development—but the same is not necessarily true for climate-tech entrepreneurs. Climate-tech startups don’t function in isolation, as they often need to be integrated into existing value chains and markets.

Climate tech entrepreneurs therefore have to navigate the complex web of regulators, incumbent corporations, existing manufacturing processes, and supply chains. They have to develop a product that meets and exceeds the specifications, standards, and requirements of an existing integrated system. This is really hard for a fresh-out-of-graduate-school team that doesn’t have industry experience or connections.

Third Valley of Death: Demonstrating the First Full-Scale Commercial Product or Facility

Another consequence of having to innovate or transform an established ecosystem is that it can be expensive and time-consuming to get buy-in from incumbents. People often refer to this valley as “death by pilots,” a.k.a the structural challenges of working within incumbents’ long and risk-averse development cycles. One founder was told by a mentor that, “trying to get a pilot with [unnamed oil major] will bankrupt you.”

Whether it is electric transport, renewable jet fuel, or even a supply chain optimization software that cuts waste, climate-tech innovators need to get incumbents to move aside or move along. However, incumbents struggle with disruptions and system changes: they often don’t see them coming, they don’t believe that they make money, they don’t know how to get them done, and they threaten incumbents’ existing business.

The resulting effect? Some startups see the only way forward is to bypass the incumbents by building a full-stack, vertically-integrated empire themselves (e.g., Tesla). Not only is Tesla designing an electric powertrain and battery system, they are also manufacturing the rest of the car and building a multi-billion dollar battery plant, as well as a national charging and dealership system. Most other startups don’t have the funding or the reach to accomplish this enormous task and instead must work with incumbents in a “cat herding” exercise.

Fourth Valley of Death: Proving that Products Are Stable, Profitable, and Scalable

Scaling up climate tech often requires orders of magnitude more capital than software deployment. This typically comes from debt or infrastructure investors, and these investors often need to see established, stable cash flows. They want to see the technical risk completely retired and assess the products or project facilities based entirely on market and operational conditions.

While it took a long time, wind and solar power are currently benefiting from an influx of institutional funders. These technologies exhibit stable cash flows as they are not exposed to volatile fuel costs and they have long-term, fixed-priced power purchase agreements with credit-worthy offtakers. But this does not apply to all climate technologies. For example, bio-based chemical plants experience feedstock and product price volatility and energy storage developers need to be comfortable with exposure to volatile wholesale electricity prices.

These new breeds of infrastructure projects require very specific skills and knowledge from investors and underwriters. It also takes time to develop these capabilities and be comfortable with the market risks involved. And here lies the last formidable valley for an emerging climate technology.

More Support for Crossing Valleys of Death Is Needed

Over the last few years, we’ve seen a renewed blossoming of climate-tech entrepreneurs, investors, and accelerators. These are great examples in bridging one or more of these four valleys. For example,

- Cyclotron Road helps bridge the first valley by discovering, funding, and championing entrepreneurial scientists and engineers.

- New Energy Nexus helps bridge the second valley by connecting entrepreneurs with investors, corporates, labs, and other resources to accelerate market discovery and new product launches.

- ARPA-E SCALEUP helps bridge the third valley by supporting the scaling of high-risk and potentially disruptive new energy technologies and helping them demonstrate a path to market.

- Generate helps bridge the fourth valley by building, owning, operating and financing sustainable infrastructure.

However, the problem illustrated above remains. It’s fantastic news that a startup has crossed one valley, but without knowing how her path will connect to the next valley and then to the next, how can early-stage investors have the confidence to act?

Investors will be more willing to back early-stage climate tech if they understand better how the downstream valleys of death can be crossed. If we can get different groups from across stages to share perspectives and collaborate upfront, then we may have a better chance of building a bridge that crosses all four daunting valleys.

The medtech ecosystem is often cited as an example of what is possible—incumbent corporates and VCs have established a reliable pathway for working with startups to commercialize innovation that is capital-intensive, that operates in highly regulated markets, and where incumbents control the sales and distribution needed to reach customers.

We are taking a new approach at Third Derivative, supporting transformative climate tech by building a comprehensive support system.

We integrate multi-stage venture capital funding; leading corporates that are keen to demonstrate, deploy and partner; and regulatory, technical, and market insights from Rocky Mountain Institute. With the clock ticking, we want to start climate-tech startups on a path that fast tracks a bridge to cross these valleys.